|

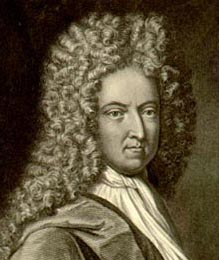

DANIEL DEFOE

Daniel Defoe (1660?-1731) [E1] [I1] [F1] [F2] [ES1] [ES2] was born in London, probably in September 1660. His father, a nonconformist merchant belonging to an extreme Protestant sect which didn’t accept certain rules or religious ceremonies of the State Church, refused to register his son’s birth in the books of his parish, so that there have always been some doubts as to Defoe’s actual date of birth.

Brought up as a Dissenter, young Daniel studied at the College of Stoke Newington, where he received a solid dissenting education. On finishing school, he chose to go into business and, in 1680, he became a merchant dealing in various products such as wine and tobacco. He travelled for two or three years in Europe on business, and, when back in England, he opened a haberdasher’s shop, got married and began meddling in politics.

In 1685 he took part in the Duke of Monmouth’s abortive rebellion against the Roman Catholic King James Il, but was able to escape punishment and, in 1688, he joined the army of William of Orange. But his business, so long disregarded, took a turn for the worse and, in 1692, Defoe went bankrupt. He managed to pay back most of his debts but, faced with the need to make up for the money lost, he ventured into many other activities, including journalism and literature, winning popularity and even the King’s friendship.

In 1702, with the accession to the throne of Queen Anne, a supporter of the State Church, his situation changed, and when he published a satirical pamphlet in defence of the Dissenters he was heavily fined, sentenced to three days in the pillory and finally imprisoned in Newgate for six months. Rescued from prison by the Tory leader Mr. Harley, in 1704 he started his famous newspaper The Review, which, written entirely by him, was to be regularly published until 1713. In exchange for Harley’s intervention, Defoe promised not to write against the government and, in 1705, he became a secret agent and government spy, supporting now the Tories now the Whigs according to which minister was in power.

In 1719, at the age of sixty, Defoe suddenly turned to the writing of prose fiction, certainly not for literary or artistic purposes, but considering it as a kind of business activity which now paid better than many others. In this field he produced a remarkable number of works, the ones upon which his actual literary fame was to rest. The last days of his life were dismal and unhappy. Compelled to adopt another pen name for concealment, he died, alone and friendless, in 1731.

When he died Defoe was about seventy years old, he had seen six kings on the throne of England and had lived through political controversies, religious persecutions, party conflicts, transformations and wars. A tradesman, a spy, a journalist and a writer, he accumulated a lot of contrasting experiences, some of which he put into his writings. One of the most prolific authors of his time, he has been credited with as many as four hundred works, besides, of course, his journalistic production. Below there is an obviously incomplete list of some of his most important works.

JOURNALISM: The Review (1704-1713), published three times a week; it was mainly political in character.

PAMPHLETS: The Shortest Way with the Dissenters (1702), in which Defoe, a Dissenter himself, ironically advocated the total suppression of all Dissenters. An evident attack against ecclesiastical intolerance, the pamphlet earned him the pillory and prison.

POEMS: The True-born Englishman (1701), a verse satire against William Ill’s enemies. Hymn to the Pillory (1703), a mock-Pindaric ode sold in great quantity among the crowd which had gathered around the pillory, where he had been put.

NOVELS: Robinson Crusoe (1719), the account of Robinson Crusoe’s life on a desert island.

Capitan Singleton (1720), relating the adventures of a captain who became a pirate.

Moll Flanders (1722), the autobiography of a woman, who was able to survive in the slums of 18th-century London by using her sex and beauty and becoming a thief and a prostitute.

Colonel Jack (1722), the story of a pickpocket, who in the end repented and reached wealth and prosperity.

Lady Roxana (1724), the autobiography of a courtesan who was finally imprisoned for debts and died a penitent.

A Journal of the Plague Year (1722), an account of the plague raging in London in 1665.

OTHER WORKS: Robberies and Escapes of John Sheppard (1722), and

Jonathan Wild (1725), on two famous highwaymen.

The Complete English Tradesman (1726), on money-getting.

5/15

5/15

|