|

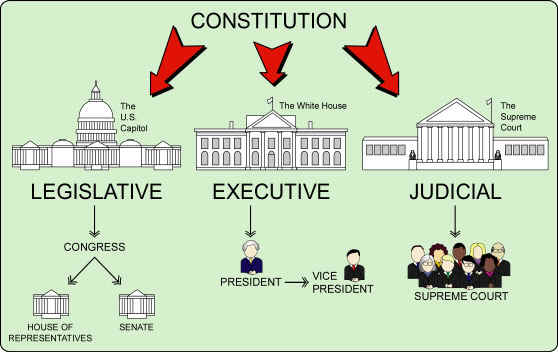

The three branches of the US Government

1. Legislative branch (Congress)

Article One establishes the legislative branch of government, the United States Congress [E1][E2][F][Es1][Es2][I], which includes the House of Representatives (“composed of members chosen every second year by the people”) the Senate (“composed of two Senators from each State, for six Years; and each Senator shall have one Vote”).

The Constitution states that “All bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives; but the Senate may propose or concur with Amendments as on other Bills. Every Bill which shall have passed the House of Representatives and the Senate, shall, before it become a Law, be presented to the President of the United States; If he approve he shall sign it, but if not he shall return it, with his Objections to that House in which it shall have originated, who shall enter the Objections at large on their Journal, and proceed to reconsider it. If after such Reconsideration two thirds of that House shall agree to pass the Bill, it shall be sent, together with the Objections, to the other House, by which it shall likewise be reconsidered, and if approved by two thirds of that House, it shall become a Law”.

Among the powers of Congress, the “Power to lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States; […] To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States […] To coin Money”.

Many of the developments in the Constitutional system have reduced its status, particularly in relation to the President. Originally, the constitutional position of Congress had such potential that something like the legislative supremacy of a parliamentary system might have developed. During the first part of the nineteenth century, the President generally owed his position to the Congressional caucus [E] [I], and after the elections of 1800 and 1824 the House of Representatives had the Constitutional responsibility of selecting the President, because no candidate had the majority in the electoral college. In the post Civil War period, Congress again achieved dominance, and if the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson had not failed by one vote, the pattern of Congressional supremacy might have been firmly established.

The decline of legislature vis-à-vis the executive has been general throughout the West in the twentieth century. For one thing, the relative clumsiness and poor organization of large representative bodies put them at a disadvantage: the executive is always in session, capable of moving quickly to formulate programs and meet emergencies.

If the status of Congress is perhaps less than was contemplated when the Constitution was adopted, its range of legislative responsibilities is much greater. From the limited, laisez-faire goals of eighteenth-century legislation, we have moved to the twenty-century welfare state, where Congress accepts responsibilities for assuring full employment, education, medial care, social security, public health and a hundred other imperatives of modern American life. The Constitutional foundation for this tremendous expansion in the activities of Congress has readily been found in the language of the Constitution, particularly in the grants of power to regulate commerce and to tax.

For a short time, between 1935 and 1937, the Supreme Court blocked such programs by a narrow interpretation of Congressional powers, but that phase soon passed. The only actual change in the Constitution required to facilitate this vast expansion of federal activities was the income-tax amendment, which made possible the financing of government at its present level. The barrier against the income tax, however, had been erected not by the Constitution but by a highly questionable Supreme Court interpretation.

2. Executive branch (the President)

Article Two describes the Presidency [E][F][Es][I]. According to the Constitution, the President “shall hold his Office during the Term of four Years, and, together with the Vice-President chosen for the same Term, be elected, as follows:

"Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress: but no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector”.

“The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States […]. He shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur; and he shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court”

“He shall from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient”

“[The President] shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors”.

The American Presidency has now evolved into the most powerful executive in the democratic world. The foundation for this development was laid by the founders of the Constitution, who overcame their doubts about strong executives in inventing this new office. They equipped it with tremendous authority – the power to appoint, to recommend legislation, to supervise the executive developments, to act as Commander in chief, to assume control of foreign relations.

The one great modification in the original plan for the Presidency – the method of selection – occurred without any significant change in the language of the Constitution. The electoral college [E1][E2] [F] [Es] [I] was retained, but the electors, who were initially free agents in casting their votes, quickly became automatons registering the results of the popular vote in their states. As the choice of the national electorate, the president can now claim, even more than Congress, to represent the national will, and the direct link to the electorate has supplied the one element needed for the full development of the presidential office.

The vice presidency [E] [F] [Es] has also been substantially modified by practice, although much more recently. This office, created at a late stage in the Constitutional Convention, was given the task of presiding over the Senate, even though this seemed an infraction of the principle of separation of powers, largely because it was feared that the Vice President would otherwise have nothing to do. In fact, for a century and a half, the Vice President had little to do anyway. Since President Eisenhower’s terms, the office of vice President has acquired a new structure and significance in the America political scene, and in 1968, for the first time since the election of 1800, a Vice President and a former Vice President were opponents for the Presidency.

3. Judicial branch (Supreme Court)

Article 3 states that the Judicial power “shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. The Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behavior”.

“In all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party, the supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction. In all the other Cases before mentioned, the supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction […]. The Trial of all Crimes, except in Cases of Impeachment, shall be by Jury”.

The Supreme Court [E1][E2][F][Es][I], like Congress and the Presidency, has had ist up and downs, but in general it has much exceeded the expectations of 1787. Alexander Hamilton in No. 78 of The Federalist spoke of the Court as the “least dangerous” of the branches, possessing “neither force nor will, but mereley judgment”. However, the role of ultimate interpreter of the Constitution earned such prestige for the Court that it has almost always emerged unscathed from its numerous controversies with the President and the Congress. Since 1954, when the decision banning racial segregation in the public schools was handed down, the Court has assumed on an unparalleled scale the role of moral leadership in the political drive for equality and civil rights.

5/8

5/8

|